You’re accessing archived content

This is archived content from the UIT website. Information may be outdated, and links may no longer function. Please contact stratcomm@it.utah.edu if you have any questions about archived content.

UIT’s Lovett, Sallay making PPE for frontline workers

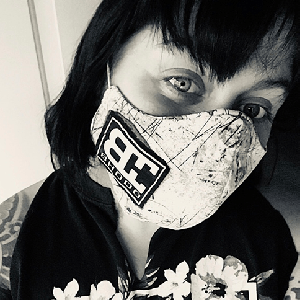

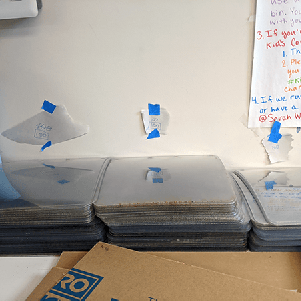

Jan Lovett's grandson, Max, models a mask that she made. (Courtesy of Jan Lovett)

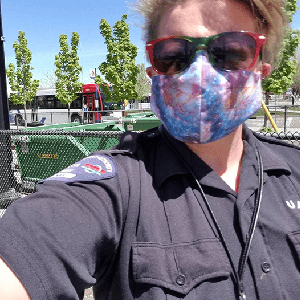

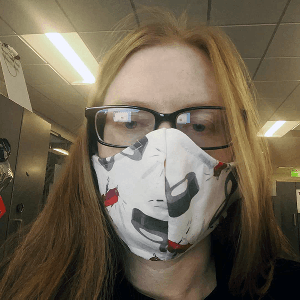

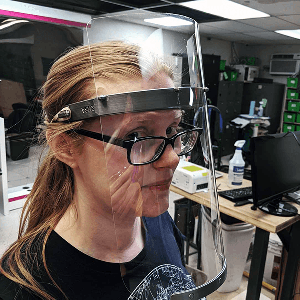

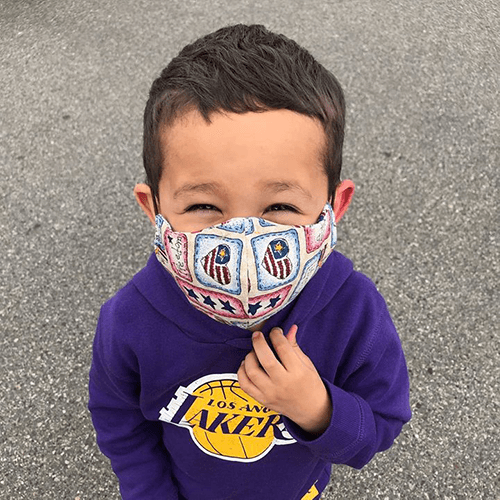

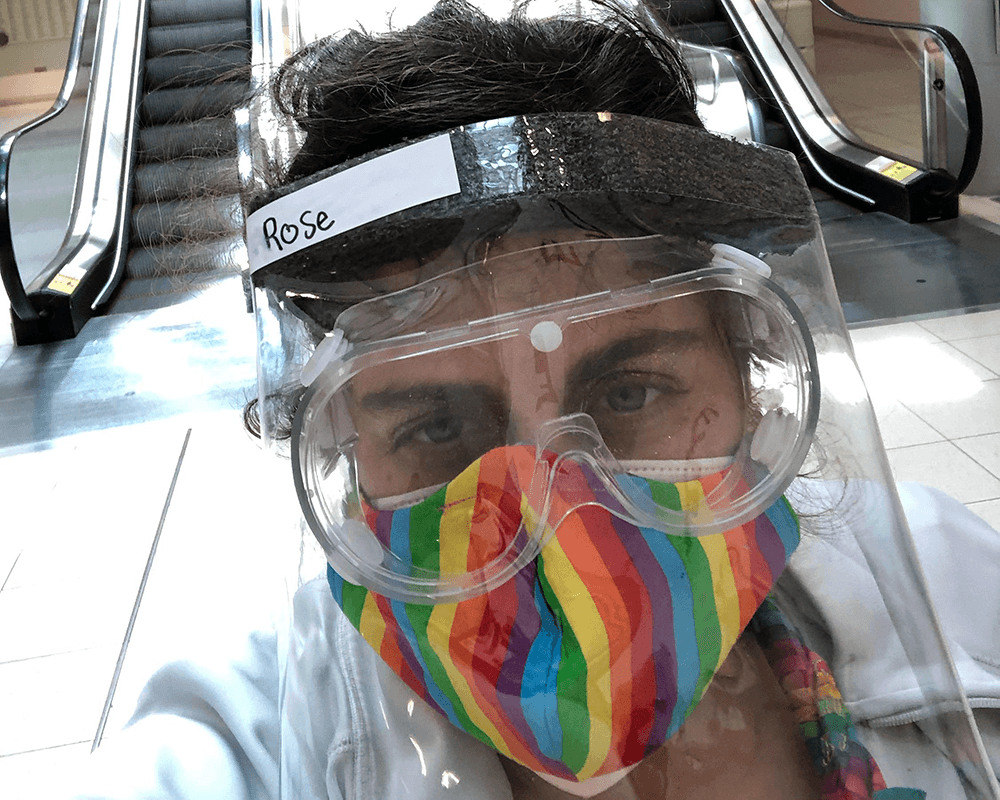

Beth Sallay models a face shield that her team 3D printed and laser cut at Make Salt Lake as part of its COVID-19 PPE project. (Courtesy of Beth Sallay)

Jan Lovett wondered if she could remember how to sew. She hadn’t touched her Baby Lock machine in the past eight or nine years, but she had learned to sew as a child and had sewn most of her life.

But she did know that she couldn’t sit idly by as those on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic faced the virus without proper protective gear.

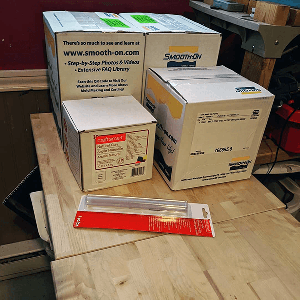

So Lovett, an IT product manager in University Support Services, began to make fabric face masks. About the same time, Beth Sallay, a systems administrator in Campus Computer Support, began work with her colleagues at Make Salt Lake (MSL) to manufacture protective face shields.

Lovett said she started making nonmedical-grade face masks because she kept hearing about people, particularly medical professionals and essential workers, who were unable to access protective personal equipment (PPE) or had limited supplies.

“The first person I gave a mask to had posted on Facebook that [her employer] gave her one and that she had to write her name on it and reuse it every day. And she's in a medical setting,” Lovett said. “Are you kidding? This is how we’re treating the people who are there to help everybody?”

Sallay, who has volunteered at MSL for more than five years, said the nonprofit’s PPE project was first suggested in the group’s Slack channel. Many makers, she said, felt the need to step up because the government wasn’t really helping out. Sallay also felt angry when she learned that some medical professionals had been using plastic report covers to shield their faces.

“I was so mad — not that we had to do this, but that it had come to that. Make: Magazine is calling this ‘Plan C,’ which is basically homemade arts and crafts,” Sallay said. “Now I kind of feel like, we have your back, but at the same time, we really shouldn't have to.”

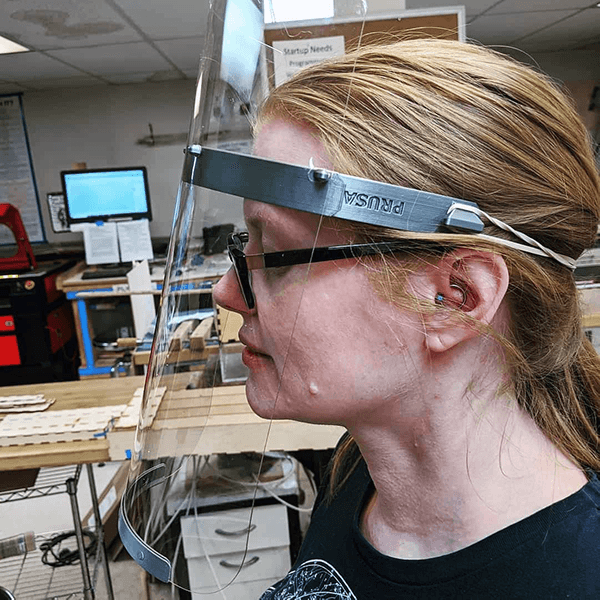

A fake skull with a sign points to where people should drop off 3D-printed and laser-cut pieces to make face shields at Make Salt Lake. (Courtesy of Beth Sallay)

3D printers, laser cutters used to create face shield components

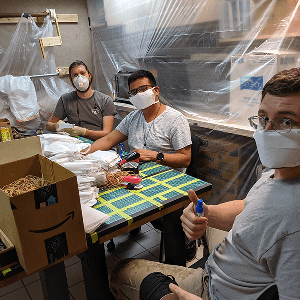

Sallay spends most evenings and Saturdays at MSL, generally splitting her time between teaching others how to use the laser cutter and cutting the materials to build face shields. She estimated that she devotes about 15-20 hours a week there, although she spent a lot more time on the phone and Slack when MSL started to gear up for the project.

Beth Sallay

MSL’s effort comprises three phases — filtered masks, fabric masks, and face shields. Sallay is the project lead for Phase 3, which focuses on protective 3D-printed and laser-cut face shields for health care workers. She oversees a team of five to 10 makers, although she said many more volunteer with the organization.

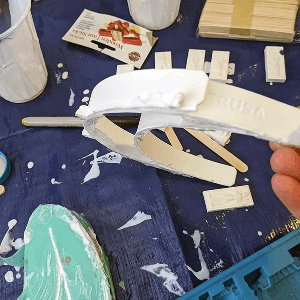

The initial face shield design, developed by Prusa Research and the Czech Health Ministry, came from the National Institutes of Health, but Sallay has been modifying it as MSL receives feedback from medical professionals.

“If someone says, ‘This part is hurting.’ Then we change it a little bit,” she said, noting that she also maintains and updates all the Phase 3 documentation outlining how to produce the protective gear.

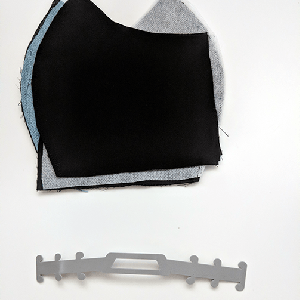

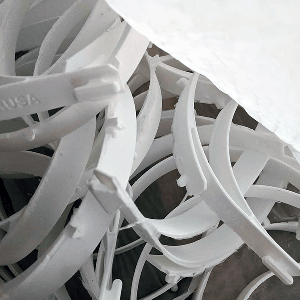

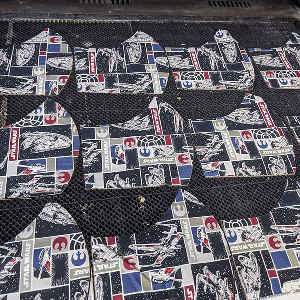

The face shields are composed of three parts: a heavy-duty plastic shield, a headband, and a reinforcement band at the bottom of the shield.

Support Make Salt Lake

To learn more about Make Salt Lake’s COVID-19 PPE project, please visit the MSL blog. To learn more about volunteering, or donating funds or materials, please visit the MSL COVID-19 PPE project page.

The materials and methods differ, depending on supplies and time, much of which has been donated by community members, and MSL workers and volunteers themselves. For the shield, Sallay has used PETG and PLA plastic, and even acetate.

“We were running out of the PETG plastic for the face shields; no one could find it anywhere. So we were like, ‘What the heck are we supposed to use?’” she said. “… Someone said, ‘We're going to use acetate,’ and I'm like, that's overhead projector material. As it turns out, I was making view finder reels out of that, like a year ago, and I had a roll of it.

Right now, her team is cutting shields from a 550-pound roll of PETG plastic that had been donated by someone from Masks for Docs. Sallay can make six shields in about five minutes.

“I don't know how many feet or miles that is, but we need to get 3,000 face shields out of it. And the goal is to not waste any material,” she said.

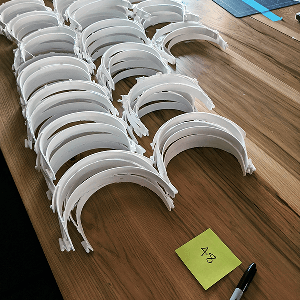

The headbands and reinforcement bands are typically 3D printed, although one volunteer also made some with injection molds, cutting the process from about five hours to about three seconds. Since MSL has only three 3D printers, Sallay’s team relies on volunteers to help make the headbands.

“Everyone involved is just amazing. So many people are helping, and we don't even know who they are because they're doing it anonymously. People also are buying 3D printers, giving them to us to use for the duration of this, and then we’ll give them back or they're donating them to the makerspace.”

So far, MSL has distributed hundreds of face shields, with 450 shields and 150 3D-printed headbands ready to be assembled and shipped out. Sallay, however, still worries that what they have in stock will not be enough when the virus reaches its peak.

“I always feel like it's not enough,” Sallay said. “We're not New York, but very easily we could be.”

Each mask created by Jan Lovett has two fabrics, elastic bands, and a nose piece. (Courtesy of Jan Lovett)

Fabric mask pattern required a lot of research, trial and error

Lovett began creating face masks about the same time U employees started working at home. She’s been at it almost every day since then.

“I will start after work. I might eat dinner, go back into my office/sewing room, and sew until midnight or so,” she said. “And then a lot of times when I'm watching TV, I'm cutting out fabric, because you have to hand cut all these things and it takes forever.”

Jan Lovett

A friend who quilts provided about 4 yards of fabric for her first batch, which she modeled after a pattern posted on YouTube by a quilter and former nurse who lived in Washington, a state that was hit particularly hard early on by the coronavirus. Like Lovett, the woman had spent a considerable amount of time researching fabrics, elastics, and linings.

“After looking at everything, I used hers because she was a nurse. She knew, medically, what could be used and what couldn't,” Lovett said.

Each mask has a layer of 100 percent cotton, a lining of non-woven fabric called OLY-Fun, elastic bands, and a nose piece made from aluminum pans.

“I just got cheap aluminum pans from the Dollar Store — believe it or not — and cut out the bottoms and cut them into strips. Then I folded them so there weren't any sharp edges, and you can sew right through them,” she explained.

While the nose pieces help mold the mask to the face, the fabrics offer protection by keeping droplets from entering and exiting. She said she uses fabrics with different patterns, so it’s easy to tell which one goes on the outside.

Lovett has made a few tweaks since then, adjusting based on fit and feedback.

“I've learned that sometimes the gaps on the side of the masks are too big and you need to figure out how to adjust those,” she said. “The other thing that became really apparent early on is how irritating the masks are to people who have to wear them all the time.”

In response, she ordered cord stoppers, which she has yet to receive, and mask straps to alleviate pressure on the ears from the elastic bands.

Lately, though, she said it’s become more difficult to find supplies. Since Lovett avoids going into stores to shop, she spends a lot of time online trying to find what she needs for a fair price and within a reasonable delivery date.

By the time she gets the fabric, she has to stitch the sides before she washes it in hot water and dries it — twice. After she irons the fabric, she cuts eight pattern pieces for each mask, then the elastic and aluminum.

“It is quite a process.”

At times, when she feels like she’s not producing a batch of masks fast enough, she will change her routine and go back to making one at a time. The hard part, she said, is having enough prewashed and precut materials on hand so she can switch tasks when she tires of another one.

The project, she admitted, has been a bit consuming, but she’s had some help along the way.

“I take over the dining room table when I need to cut fabric because I don't have space in my office to do that,” Lovett said. “And I have to give a shout-out to my husband because he’s been fixing me dinner and cleaning the house while I sew — he's been really helpful.”

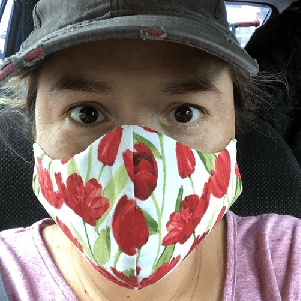

A medical professional takes a selfie wearing one of Lovett's masks. (Courtesy of Jan Lovett)

Efforts help frontline workers all over Utah

Lovett has made more than 200 masks. With the help of her friends, she’s donated them to an assisted living facility in Utah County, local nurses, postal workers, police officers, families, high-risk individuals, and the staff at Wasatch Broiler and Grill in Midvale.

“I've been trying to donate all of this because I kind of feel like that's something I can do,” she said. “I still have a job, and I don't really want people to pay for the masks. So I've asked people to make a donation to a charity.”

One person decided to pay it forward by providing Lovett with more fabric.

“I had given her a bunch of masks and I had run out of fabric. She said, ‘I'm going to the store and I'll get it for you. Tell me what you need,’” she recalled. “She brought me like 5 yards of fabric, and you can make about 10 masks out of 1 yard. So that helped a lot until I could get my other fabric in.”

Sallay said MSL had given away 4,000 pieces of PPE since the project started. They’ve donated to the Navajo Nation, local medical centers, Gold Cross Ambulance, a women’s shelter, jail, University Neuropsychiatric Institute, a homeless resource center — just about any organization with high COVID-19 exposure that requests them.

Before delivery, Sallay disinfects the face shields going to health care organizations, which must sign a waiver acknowledging that the PPE is homemade and disinfected to the best of their ability.

“Whatever precautions we use to sanitize what we give them is going to be nothing compared to what they're going to do,” Sallay said. “They’re the experts on it.”

Although she spends 99 percent of her time on the shields, Sallay also has sewn about 30 fabric face masks that she gives to people who ask for them, as well as essential workers.

“I made 15 masks that I carry around in my car, and I'll offer them to service workers, like someone at the grocery store who doesn't have one,” she said.

For the foreseeable future, Sallay and her team will continue to focus on turning the 550-pound roll of plastic into more shields. Once that runs out, she expects MSL will rely on fundraisers and donors to provide supplies. If that doesn’t work, the makers will pitch in again.

“We would probably go back to where we were before, which was not really sustainable, but the majority of members donating,” Sallay said.

She plans to keep going until she runs out — “out of full capacity, energy, I don't know what.”

When that happens, she hopes to have a memento to remember “this crazy time.”

“I started saving little scraps of fabric [from the MSL masks] because hopefully someone else will be willing to make a quilt,” Sallay said. “I still ask people, ‘Can you save a little bit of the fabric so we can remember what people did?”

Lovett also is staying the course, although she briefly considered joining Project Protect. Ultimately, she decided her work filled a need not met by that initiative.

Right now, she has a good stock of fabric. And she’s finally gotten around to sending some out to family in Georgia, Nevada, and New Jersey.

Everyone, Lovett said, should be wearing a mask.

“I'll just keep making them until no one needs them anymore.”

Node 4

Our monthly newsletter includes news from UIT and other campus/ University of Utah Health IT organizations, features about UIT employees, IT governance news, and various announcements and updates.